It’s Bicycle Day.

getty

April 19 is a big day every year for people who love psychedelics. It is the anniversary of a momentous, stoned bicycle ride taken in 1943 by Albert Hofmann, the chemist who first synthesized both LSD and psilocybin. While working for Sandoz Pharmaceuticals in 1938, he had synthesized LSD from ergot, an invasive fungus that infects rye. Five years later he accidentally scratched some LSD into his skin. Intrigued by the mental changes he experienced, he purposefully ingested 250 mg of the drug a few days later; that was a whopper of a dose. Hofmann asked his lab assistant for help getting home. They both got on their bicycles, and the assistant escorted him to safety. Today on April 19 we celebrate that Hofmann made it home at all and that the psychedelic era was launched.

To be honest, though, primitive cultures had been taking various forms of psychedelics for millennia, incorporating them into spiritual and healing rituals. Hofmann’s bicycle ride home on April 19, 1943, only marks the beginning of the psychedelic era in the developed world.

This is the story of an exceptional, Harvard University study of the effect of psilocybin on spirituality and mysticism. The study was conducted in 1962 during the heyday of the Harvard Psychology Lab’s experiments with psychedelics. As controversial as nearly all of the studies from the Lab became in later years, this particular study’s conclusions have been supported by those of two far more recent examinations of the psilocybin/spirituality association.

The Experiment

The 1962 experiment now has two nicknames: The Good Friday Experiment and the Marsh Chapel Experiment. Mike Young, now a retired Unitarian minister living in Honolulu, was one of the study participants, and he is fairly well convinced that participation in the study helped transform his life.

Young was one of the Andover Newtown Theological School students who participated in the study. Its stated purpose was to assess psilocybin’s ability to create strong spiritual and mystical experiences. The experiment was designed and run by Harvard Ph.D. candidate Walter Pahnke.

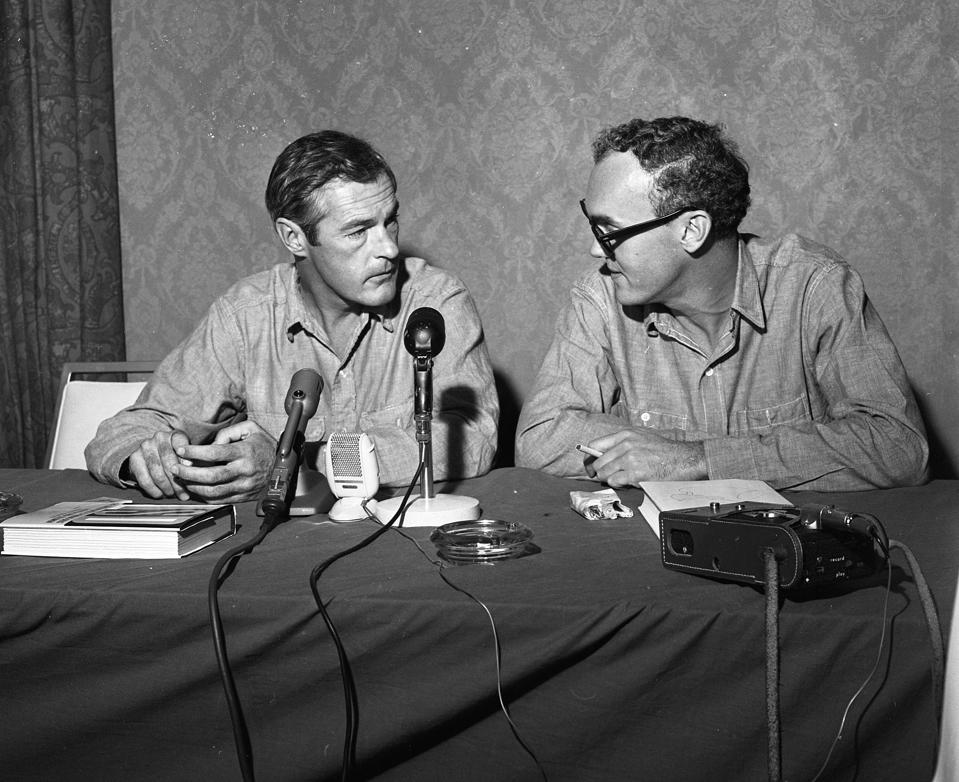

Timothy Leary and Richard Alpert. (Photo by John McBride/San Francisco Chronicle via Getty Images)

Hearst Newspapers via Getty Images

At the time, psychedelic experiments at Harvard were loosely supervised by professors Timothy Leary and Richard Alpert. With their agreement, Pahnke brought the twenty divinity school students into a room underneath Harvard’s Marsh Chapel. Upstairs, Howard Thurman (then a graduate student and later a prominent theologian and civil rights leader) was giving a Good Friday sermon. It was piped into the room holding the study participants.

Ten of the participants were given psilocybin in pill form, and ten received a placebo. No one —neither the students nor the people helping Pahnke run the experiment — knew who’d gotten the placebo and who’d gotten psilocybin.

Young received psilocybin.

Young: It was maybe 40 minutes after taking the pill that I began to feel stoned. The first clue was that the lights began to have halos of different colors around them. I experienced myself slide into what came to be like the middle of the ocean. Currents of different colors were flowing through me, as though I were at the center of a giant mandala. I believed that I was required to swim out of one of those to a whole different life experience but I couldn’t choose which color current to swim out of. So I died. I was so anxious. Dying felt like hell. It felt like my guts were being ripped. While I was at the peak of my dying I heard the piped-in Howard Thurman sermon. He was reciting lines written by the poet and playwright Edna St. Vincent Millay.

“I know that I must die, and this I will do for death: / I will die. But no more. I am not in his employ.”

Right then and there, I quit dying. From there on out the psilocybin “trip” was a relatively pleasant visual experience that I thoroughly enjoyed.

The day of the experiment wasn’t nearly as agreeable for another one of the 20 students. He fled the chapel for Commonwealth Avenue, overwhelmingly anxious to fulfill what he believed was his just-received appointment to go out and announce that Jesus would rise from the dead. That student had to be injected with Thorazine.

Surprise: that student had received the placebo.

Young: After the trip, we were all asked to dictate our experience into a tape recorder and then to write about our experience on a piece of paper. The student who’d had to be injected with Thorazine claimed to have had a religious experience. I said I had not had a religious experience, probably because even though I was a divinity student I had a narrow notion of what religion and spirituality were all about. I thought that Pahnke was asking whether I’d had a heightened experience of religious imagery and language. My trip hadn’t been like that at all.

Hallucinations of angels, chants, and virgins were actually not what interested Pahnke. He wanted to learn whether psychedelics could cause permanent and beneficial spiritual transformations.

Young: A year after the Good Friday Experiment I knew that I’d probably had what Pahnke might have thought qualified as a religious experience. Before the Experiment, I’d thought it would be fun to get a theology degree, maybe a medical degree, and maybe a law degree. After taking psilocybin, though, I began building a life of social activism. I became a minister, but not an ordinary one. Beginning in the 1960s I was up to my ears in the anti-war movement and the humanist psychology movement. The anti-draft organization for the Bay Area met at my house. I spent 21 days in jail for trying to stop the war, and I worked frequently with the Haight Ashbury Clinic trip-sitting people on bad acid trips. I did some things to get rid of the bad drugs that were on the street. A group of us used to go out and buy drugs and take them over to the lab at UC Berkeley and test them. Then we’d publish in the local underground newspaper the results of the tests as a way to try to get a little more safety on the street for the kids using drugs. Down in Los Angeles, I worked with juvenile offenders. I helped reduce recidivism. In Florida, I helped create the Florida Consumer Action Network and then joined a Black social action movement. I was given the Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Drum Major for Justice Award by the Black community in Tampa. And so on, for 51 years. So: did psilocybin create in me a lasting spiritual change? There’s no way to tell for sure, not without doing a double-blind experiment that shows me my “with psilocybin” life alongside my “without psilocybin” life. And, anyway, rather than asking about whether psilocybin has a religious or spiritual effect, it might be better to ask whether a psychedelic experience can reframe your values. I think it might have for me.

Pahnke’s dissertation, published in 1963, claimed that almost all Good Friday Experiment participants who received psilocybin experienced positive mystical or spiritual transformations. They reported those transformations immediately to Pahnke after their trip and they did six months later, as well.

Supporting Studies

Rick Doblin (AP Photo/Gregory Bull)

ASSOCIATED PRESS

Twenty-five years after Pahnke’s 1962 experiment, the conclusions from his study were essentially ratified by a researcher at the New College of Florida. Graduate student Rick Doblin created a 25-year follow-up to Pahnke’s 1962 Good Friday Experiment. He interviewed Mike Young and the other original participants in Pahnke’s study. Nine of the ten people who’d been part of the psilocybin group described their experience on psilocybin to Doblin as having elements of a genuine mystical nature. Indeed, according to Doblin, they characterized it as one of the high points of their spiritual life. (Doblin is now the founder and executive director of the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies, which helps hospitals and universities gain regulatory approval for studies of controlled substances.)

By 2006, researchers associated with Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore had also become intrigued by the apparent power of psychedelics. They applied for permission to work with what, since the late 1960s in America, had been classified as Schedule 1 controlled substances. With the Council on Spiritual Practices in San Francisco, they received Federal permission for a limited experiment on the effect of psilocybin on mystical and spiritual experiences.

Psilocybin mushrooms. (Photo by Joe Amon/MediaNews Group/The Denver Post via Getty Images)

Denver Post via Getty Images

Even though the researchers intended to replicate the findings of the Good Friday Experiment, there were a few significant differences in the design of the two studies. In the new, 2006 work, study participants took their psilocybin individually rather than in a group setting. The experiment was conducted in a hospital setting, not in a room underneath a chapel into which a sermon was being piped. The doses of psilocybin given in the new experiment and in the 1962 Good Friday Experiment were equal; they were 30 mg. However, in the Good Friday Experiment, the placebo was Niacin, which is one of the B vitamins; it can cause a feeling of heat and a flushed face. In the new experiment, the placebo was not entirely inactive psychologically. It was methylphenidate hydrochloride, which is the generic name for Ritalin; it is commonly used in the treatment of attention deficit disorder. The new study took place over eight sessions as opposed to one session for the Good Friday Experiment.

During the active drug stage of this new study, volunteers were asked to close their eyes and direct their attention inward. Participants answered questions about their psilocybin experiences shortly after each trip and again about two months later. As had been true for Mike Young, the veteran of the Good Friday Experiment, some of the psilocybin experiences for participants in the new study included significant episodes of anxiety. More significantly, perhaps, by and large, the participants had significant mystical and spiritual experiences or shifts in perspective, just as Young had in 1962. Writing in the peer-reviewed journal Psychopharmacology, the researchers from Johns Hopkins and the Council on Spiritual Practices noted that, “At 2 months, the volunteers rated the psilocybin experience as having substantial personal meaning and spiritual significance and attributed to the experience sustained positive changes in attitudes and behavior consistent with changes rated by community observers.”

Timothy Leary, Richard Alpert, and Waltner Pahnke are all long dead. By 1963, Leary and Alpert had become so enamored of psychedelics that their behavior may have bordered on evangelism. They had also become increasingly irreverent and rule-breaking, and it eventually cost them their positions at Harvard. When they left, psychedelic research at Harvard stopped.

Leary got arrested on minor drug possession charges several times. At one point in the 1960s, sentenced to serve six months to ten years in a minimum-security prison in California, he escaped with the help of the Weathermen, an American radical group committed to political violence. He successfully fled the country, but life on the lam wasn’t good to him. Arrested periodically overseas only to be returned to America until he fled again, Leary spent time inside 36 prisons. Eventually, he became an FBI informant. Rewarded for his cooperation, he was released from prison for good, though for a while he had to live in the witness protection program. He finished out his life in a comfortable home in the Laurel Canyon neighborhood of Los Angeles. He also did a considerable amount of touring with Watergate burglar G. Gordon Liddy; he and Liddy debated social and political issues for pay and applause. Leary’s late-life interests included space colonization and computers. He died in 1996 of prostate cancer, having finished writing the book Design for Dying, which was published after his death.

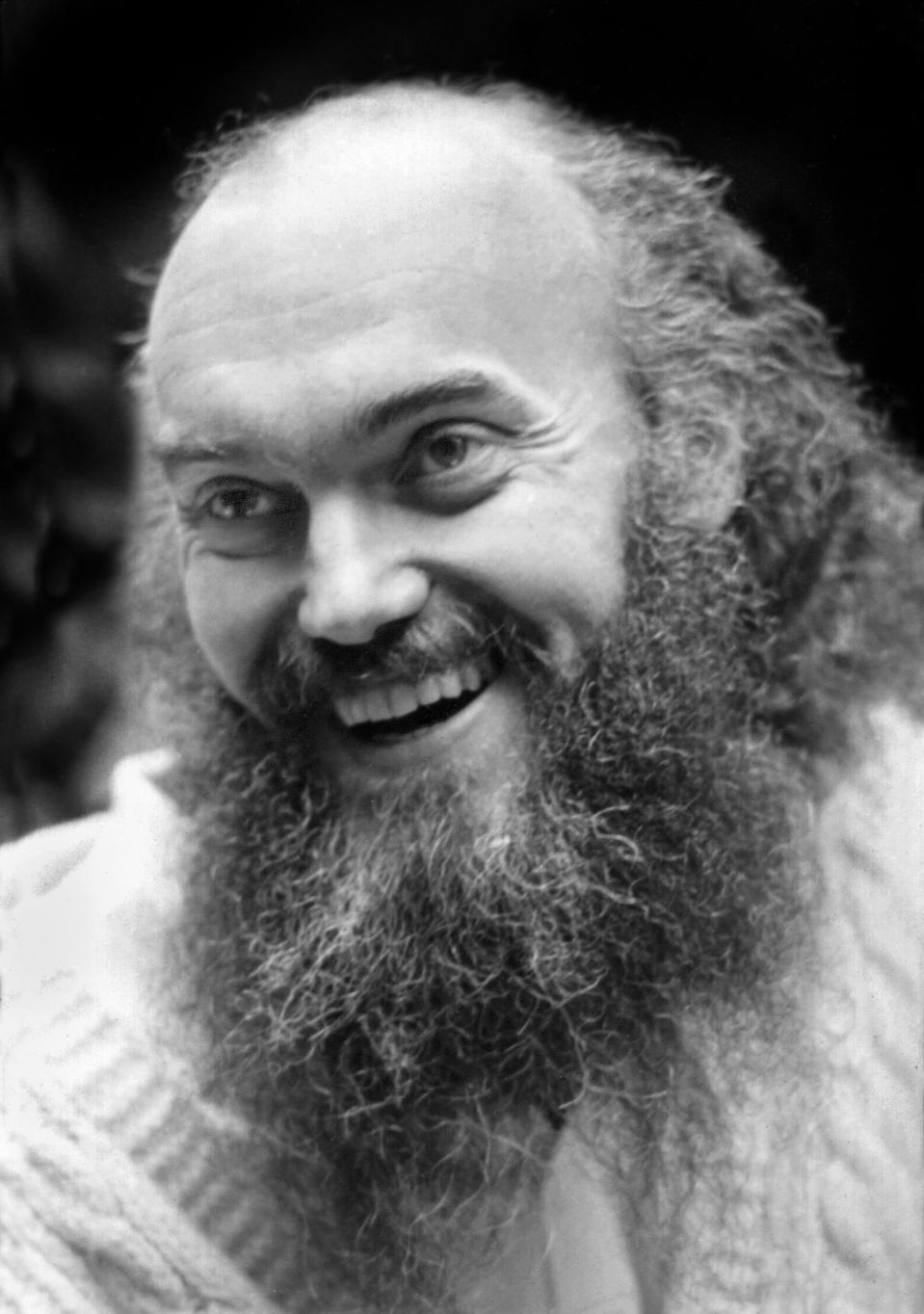

American spiritual teacher Baba Ram Dass (Richard Alpert) on January 2, 1970 in San Francisco, … [+]

Getty Images

After leaving Harvard, Richard Alpert traveled to India and became a devotee of the guru Neem Karoli Baba, who gave Alpert the name Ram Dass. It means “servant of Ram,” who is a major Hindu deity. As Baba Ram Dass (“Baba” is a term of respect meaning “father) he founded several charitable organizations and wrote the best-selling book Be Here Now. In the 1990s he began openly discussing his bisexuality. In 1997 he had a stroke and lost use of his left arm. He also suffered from stroke-related aphasia, which is a disorder impairing the understanding and expression of language. Once he recovered his ability to talk and write, he moved to Maui and continued to teach, write books, and host conferences until he died at home at the age of 88. The family didn’t announce the cause of death.

Walter Pahnke graduated from Harvard Divinity School, Harvard Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, and Harvard Medical School. While psychedelics were still legal in the United States, he used them to assist in psychotherapy for people suffering from alcoholism and certain mental health disorders. He died in 1971 in a scuba diving accident.

What’s Next

· Psilocybin’s use in psychotherapy for depression, anxiety, suicidal thoughts, and substance abuse is impressive. It does not seem to contribute to criminality, and it may even have general health benefits.

· The state of Oregon has mandated the creation of a network of psilocybin service centers through which psilocybin can be distributed and people can receive supportive, psychedelic-assisted mental health therapy.

· Just in the past few weeks, studies have shown that small doses of psilocybin can reduce depression as well as commonly prescribed anti-depressants.

· While psilocybin has a reputation for improving divergent thinking, researchers have found that it actually impairs productive creativity, at least during the psilocybin trip. A week after the trip, though, is a different story. Creative insight may be part of what psilocybin bequeaths long-term.

Prejudice against psilocybin was born in the late 1960s, some say in reaction to the lack of hygiene and manners in some members of the counterculture. This year, 2021, might be the year to drop the revulsion. Psilocybin is showing enormous potential to change lives for the better. Controlled, larger population studies are being designed to determine if it’s truly as safe and effective as some researchers suggest that it is. If it can help trained therapists drive back addictions and mental health problems and, all the while, ramp up transformative, spiritual experiences, . . . well can we at least wish the once-maligned drug good luck?