On Thursday, the Centers for Disease Control’s expert advisory committee on vaccines met to vote on new guidelines for the use of boosters to sustain the immunity provided by the COVID-19 vaccines in use in the US. The day prior, the Food and Drug Administration issued an emergency use authorization (EUA) that greatly expanded the number of vaccinated people who could receive a booster shot. That set the stage for the CDC to determine whether the FDA approval should be adopted as formal health policy.

A key step in the CDC’s policymaking process is approval by its Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). While the CDC director isn’t bound to follow ACIP’s advice (and notably didn’t in an earlier booster decision), overruling ACIP is unusual. Given that ACIP has now voted unanimously to expand booster use to Moderna and Johnson & Johnson vaccine recipients, the CDC director will likely follow its guidance.

FDA sets the stage

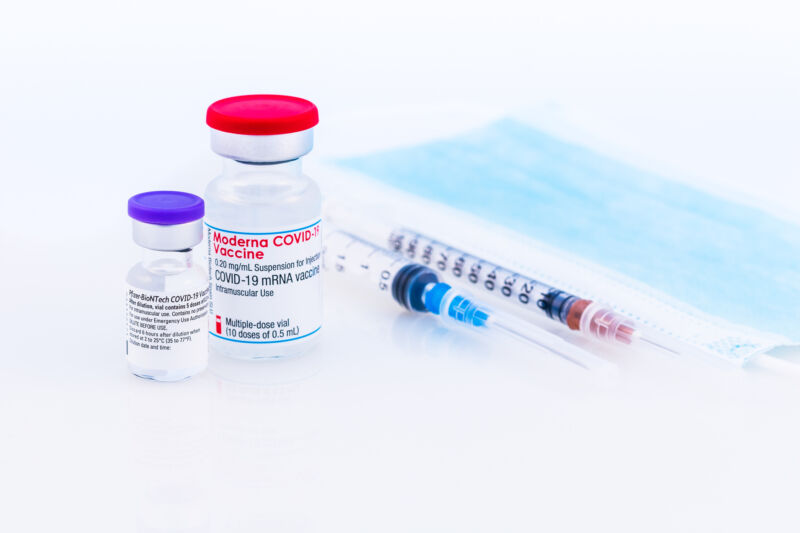

On Wednesday, the FDA announced that it was expanding its EUA for COVID-19 vaccine booster shots. Earlier this month, the FDA approved Pfizer/BioNTech boosters for people who are six months out from receiving their initial doses and are at risk of exposure (like health care workers) or severe COVID cases (the elderly and those with health conditions). The CDC approved this guidance despite a split vote against it from its advisory committee.

The FDA gives the same guidance to recipients of the Moderna vaccine as it gave for the Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine: It is approved for those over 65 years of age, those with medical conditions that place them at risk, and those with a job that increases their exposure to infections. For those who received the J&J shot, anyone over the age of 18 can get a second shot as soon as two months after their prior one.

The FDA also acted on evidence that mix-and-match boosters are highly effective. Accordingly, anyone who qualifies for a booster based on any of the rules described above is now authorized to receive any of these three vaccines.

The FDA’s EUA, however, is simply a determinant of what’s allowed. The CDC separately sets a policy for its preferred approach to vaccinations, based on the advice of ACIP—although as we saw earlier this month, the CDC director overruled some of ACIP’s advice. The CDC’s guidance is often taken into account by state and local health departments, insurance companies, and others, so it has a significant impact on how the FDA’s authorizations are put into practice.

Data, so much data

Anyone who worries that we don’t have the data to know enough about these vaccines—a group that sadly includes Florida’s new surgeon general—should be forced to sit through the hours of presentations that the ACIP receives before voting. We now have multiple clinical trials (both industry- and government-funded) and several platforms for tracking adverse reactions among the vaccinated. And the numbers in some cases are staggering: Between clinical trials and ad-hoc boosting, the CDC has tracked nearly 11 million people who have already received vaccine booster doses.

While covering all the data is impossible, there were a number of recurring trends. One is that the rate of side effects from boosters is not significantly different from that of the initial vaccination. The most significant issues (heart inflammation from the RNA vaccines, clotting problems from the J&J) remain rare, and no new issues have been identified. Mostly, people get a bit feverish, achy, and/or tired.