With a new session of Congress underway and a new administration in the White House, Big Tech is once again in lawmakers’ crosshairs. Not only are major firms such as Apple, Amazon, Facebook, and Google under investigation for allegedly breaking existing antitrust law, but a newly proposed bill in the Senate would make it harder for these and other firms to become so troublingly large in the first place.

The bill (PDF), called the Competition and Antitrust Law Enforcement Reform Act (CALERA for short, which is still awkward) would become the largest overhaul to US antitrust regulation in at least 45 years if it became law.

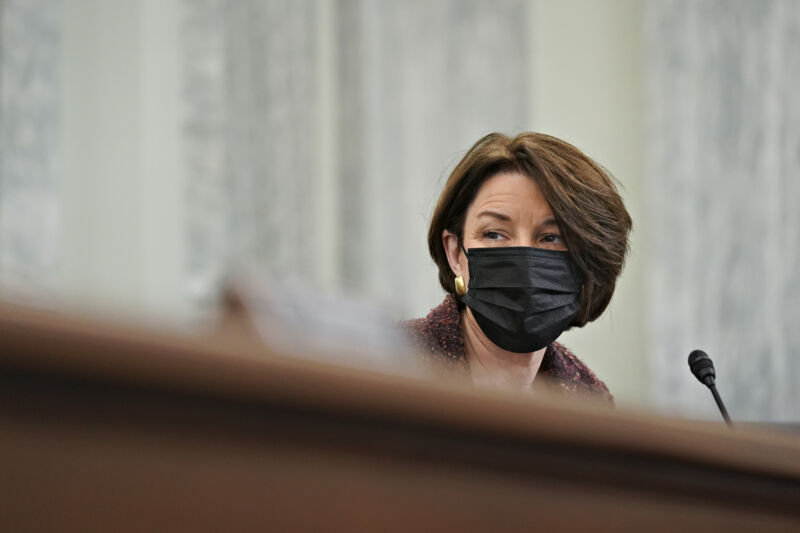

“While the United States once had some of the most effective antitrust laws in the world, our economy today faces a massive competition problem,” said Sen. Amy Klobuchar (D-Minn.) when she introduced the bill on Thursday. “We can no longer sweep this issue under the rug and hope our existing laws are adequate,” Klobuchar added, calling the bill “the first step to overhauling and modernizing our laws” to protect competition in the current era.

The bill proposes significantly expanded resources (i.e., more money) for the Federal Trade Commission and the Antitrust Division at the Department of Justice, to allow both to be able to pursue review of more mergers more aggressively. As Klobuchar put it to CNBC, “You can’t take on trillion-dollar companies with Band-Aids and duct tape.”

More importantly, however, the proposed law would invoke modern legal theories to update antitrust law for the way companies do and don’t compete with each other in the 21st century.

Sens. Richard Blumenthal (D-Conn), Cory Booker (D-N.J.), Edward Markey (D-Mass.), and Brian Schatz (D-Hawaii) co-sponsored the bill, which firmly targets the tech sector without actually naming it at all.

What does antitrust law do?

There have been four major antitrust bills so far in US history, all of which are aimed at preventing a single company from using unfair tactics to dominate its market sector and squash potential rivals.

Congress’s first stab at antitrust enforcement, the Sherman Act, became law in 1890. The Sherman Act was surprisingly short and simple, making it illegal to monopolize, attempt to monopolize, or conspire to monopolize a market. Once that baseline was established, the laws that followed have tried to address all the ways businesses have tried to work around it.

In 1914 the Clayton Act elaborated significantly on existing antitrust law, in large part to deal with the rush of acquisitions and formation of corporations that flowed in the wake of the Sherman Act. That law put limitations on acquisitions through stock purchases but left a giant loophole for firms that acquired other firms by buying their assets outright.

The next major antitrust overhaul, the Celler-Kefauver Act of 1950, tried to address the loopholes in the Clayton Act by setting regulations around vertical mergers (when a company acquires a business in its supply chain rather than acquiring a direct competitor) and mergers of conglomerates. Finally, in 1976, the Hart-Scott-Rodino Act put in place a rule that companies planning mergers over a certain value ($92 million for 2021) have to notify regulators and potentially face scrutiny before they complete their deal.

Switching scrutiny

All of the laws currently in place relating to review of mergers put the burden of proof in the same place: on the regulator.

When companies file their pre-merger notice with regulators (the FTC usually; the DOJ for high-profile, high-value, or particularly tricky transactions), their paperwork basically says, “We’re going to do this and this is fine.” The onus is on the regulator specifically to look for, define, and potentially argue in court reasons why the proposed transaction might not be.

Klobuchar’s bill would shift that burden in the other direction for businesses that already have a dominant market position. Those companies—which in tech would absolutely include firms such as Amazon, Google, and Facebook—would proactively have to demonstrate that a merger would not “create an appreciable risk of materially lessening competition,” in addition to not creating a monopoly or monopsony.

Mono-what?

A monopsony is effectively the same problem as a monopoly—excessively concentrated market power—but inverted. Instead of there being only one seller, a monopsony is a situation in which there may be many sellers but only one buyer.

In a classic monopoly, you have only one seller available. For example, a single oil firm has purchased all the oilfields and oil transportation companies and related businesses in the country, so if you want oil, you have to buy it from that company. In the absence of competition, that company has no incentive to be flexible in any way, including on price, and can effectively commit extortion not only on consumers but also to other businesses up and down the supply chain.

In a monopsony, you have only one buyer available—or one major buyer at least has such outsize market power that it alone can determine the way in which sellers operate and what prices they can set. In the 1990s and 2000s, for example, Walmart was routinely criticized for forcing vendors to lower prices to unsustainably low thresholds. Walmart was able to do so because it commanded such a high share of the US retail market that suppliers who wanted access to consumers couldn’t realistically refuse to work with it.

In the tech space, one could argue that Facebook, Google, and Apple each currently exert monopsony power in at least one market segment. Amazon, for example, is so dominant in the bookselling space that publishers basically can’t avoid the platform if they actually want to sell books, and that gives Amazon leverage to set terms that may be unfavorable to publishers.

Although the first known use of the word “monopsony” dates to 1933, no US antitrust law to date has ever addressed the idea of anticompetitive behavior from that sort of bottom-up direction. If it becomes law, Klobuchar’s bill would be the first to add the risk of creating a monopsony to the factors competition regulators must consider when reviewing mergers.

And speaking of “anticompetitive”…

The bill also expands the scope of what is considered unlawfully bad behavior on the part of a dominant firm.

As we’ve explained before, being the biggest—or even the only—player in a sector isn’t by itself illegal. Competition law is instead concerned with how you got there and what you do with the market power that dominance gives you. Klobuchar’s proposal would expand that threshold and prohibit “exclusionary conduct” that has an “appreciable risk of harming competition.”

That kind of legal standard might, for example, have led to a different outcome in the Qualcomm case, where the Ninth Circuit reversed an earlier judge’s finding that the company behaved anticompetitively.

“These harms, even if real, are not ‘anticompetitive’ in the antitrust sense—at least not directly—because they do not involve restraints on trade or exclusionary conduct in ‘the area of effective competition,” the court wrote in a widely panned opinion. Law that expands the definition of “exclusionary conduct” could lead to different findings in similar cases in the future.

But will it ever become law?

Six months or a year ago, any antitrust reform proposal would have been dead in the water (as Klobuchar’s 2019 reform bill was).

With Democrats currently controlling the White House, the House, and—through Vice President Kamala Harris—the Senate, however, the idea of reform actually being passed is more possible. The wheels of Congress turn at roughly the rate of frozen molasses, of course, and lawmakers on the Hill are currently prioritizing COVID-related packages… but there’s enough free-floating anger at Big Tech both in the government and in the nation at large that there’s a non-zero chance a bill of this type could, indeed, have legs.