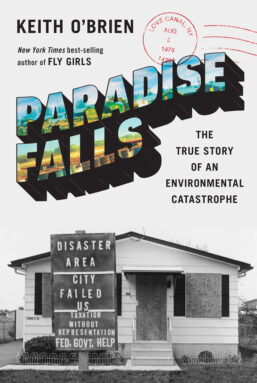

Paradise Falls

Keith O’Brien

Pantheon, $30

In December 1987, my family moved from sweltering Florida to a snow-crusted island in the Niagara River just north of Buffalo, N.Y. There on Grand Island, I heard for the first time about a place called Love Canal. Right across the river, not a mile away, lay an entire neighborhood that had been emptied out less than a decade before by one of the worst environmental disasters in American history.

In the 1940s and ’50s, Hooker Chemical dumped about 20,000 tons of toxic waste into the canal, eventually covering it with soil and selling the land to the city of Niagara Falls for a dollar. The city built a school on it, and houses sprang up around it. For years, residents would smell strange odors in their homes, and kids would see chemicals bubbling up on the playground, but it wasn’t until the late 1970s that local officials began to take notice. Eventually, testing revealed dangerous levels of toxic chemicals along with increased rates of certain cancers in adults, as well as seizures, learning disabilities and kidney problems in children.

To me as a kid, the area surrounding Love Canal was an eerie abandoned neighborhood where teenagers would drive around at night to get creeped out. The place is truly haunting. The stories I heard of toxic chemicals gurgling up in people’s backyards stayed with me, and in 2008, I returned as an environmental reporter to write about Love Canal’s legacy. Only then did I understand the magnitude of the crisis.

And only now, with the publication of Paradise Falls, do I fully comprehend the human tragedy of Love Canal and the neighborhood called LaSalle that straddled it. Journalist Keith O’Brien chronicles events primarily through the lens of the people who lived there. He focuses on the period from Christmas 1976 to May 1980, when President Jimmy Carter signed a federal emergency order that evacuated more than 700 families.

Having covered the story myself, I was puzzled at first to see that O’Brien covered such a tight time frame in a story that developed over decades. He skims quickly through the history of chemical dumping and touches only briefly on follow-up studies of residents in the 1980s. But he fills more than 350 pages with a narrative of the main crisis period so gripping it could almost be a thriller. As the disaster unfolds, there are horrific discoveries, medical mysteries and plenty of screaming neighbors. The whole narrative is pulled directly from O’Brien’s extensive research, including interviews and documents that had been stored for decades.

Chapters hop between the perspectives of key residents and the scientists and officials dealing with the crisis, but the story is told chronologically and in great detail. In fact, there’s so much detail that we even learn the type of cookies (oatmeal) served to the officials from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency who housewife-turned-activist Lois Gibbs famously took hostage in a publicity stunt.

O’Brien’s previous book, Fly Girls, was about pioneering female aviators of the 1920s and ’30s. So perhaps it’s no surprise that he has again focused on heroines. Gibbs was the public face of Love Canal, but many of the other women who took action got far less attention. O’Brien brings their stories to light. There was Elene Thornton, a Black resident of public housing who fought for her neighbors; Bonnie Casper, a young congressional aide who rallied government action; and Beverly Paigen, a scientist who risked her job studying a problem her superiors wanted to drop.

But perhaps the most poignant story, told in heartbreaking detail, is that of Luella Kenny. She was a cancer researcher living with her family in a house that backed up to a creek near Love Canal when her 6-year-old son Jon Allen fell ill with mysterious symptoms. Doctors ignored her at first, but eventually the child grew so sick he was hospitalized with a kidney disease called nephrotic syndrome.

O’Brien narrates the family’s days with stunning clarity, capturing small but moving moments like Jon Allen gathering fallen chestnuts in the hospital parking lot and rolling them between his small, swollen fingers. By the time I read of Jon Allen’s death, even though I already knew the outcome, I cried. I felt as if I knew these people personally by the end of the book, and any misgivings I had initially about O’Brien’s approach disappeared. There are many ways to tell a story, but sometimes the simplest way — the perspective of those who lived it — is best.

Buy Paradise Falls from Bookshop.org. Science News is a Bookshop.org affiliate and will earn a commission on purchases made from links in this article.