Giovanni Polverino

The mosquitofish is a particularly troublesome invasive species that has spread from its original home in North America to various locales around the world, including Europe and Australia. The small, 3 cm-long fish likes to chew the tails off fish and tadpoles and consume the eggs of other freshwater denizens.

Being an invasive species, the fish are mostly fearless, and they have no predators in the places they’ve colonized. However, an international team of biologists and engineers has found a solution to the problem: a robot.

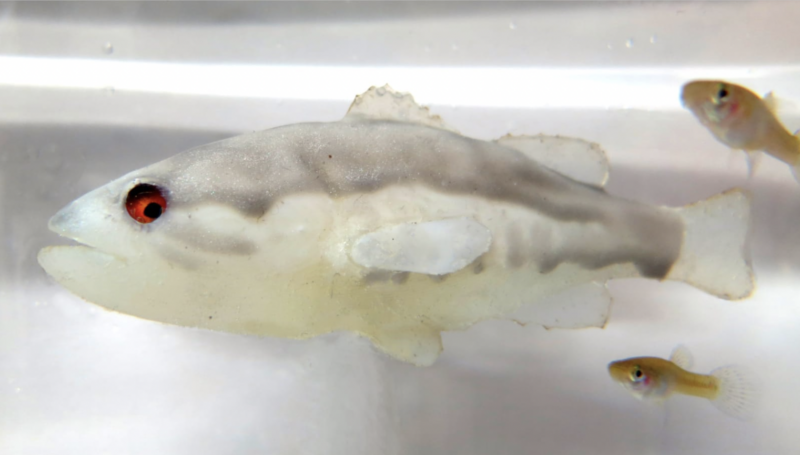

Back in 2019, Giovanni Polverino—currently a post-doc at the University of Western Australia—and his colleagues developed a mechanical largemouth bass that proved to be effective in scaring mosquitofish. In North America, juvenile largemouth bass regularly make meals of the species; the primal fear of this predator has stuck with the mosquito fish as they traversed the globe.

New research from Polverino and his team showed that this robotic bass can instill fear in the mosquitofish. The persecuted animals reproduced less and lost weight, impacting their ability to survive. “We use the fear, the innate fear that they have for this native predator,” he told Ars.

The new iteration of the robotic largemouth bass is quite advanced. In previous research, the team made the robot look and act enough like the real deal to freak out the mosquitofish. It’s now also a pretty smart machine and can recognize when mosquitofish are moving to attack other aquatic animals.

“The robot can understand what is happening between the group of mosquitofish and the group of tadpoles of the native species, and then… interrupt this action,” Polverino said.

The horror, the horror

For this new research, the team put the robot in a tank with mosquitofish and other Australian native species. When the mosquito fish went to eat the native species, the robo-bass would intervene, scaring them off. None of the Australian species had any history with largemouth bass and were thus unafraid.

“The species in Australia are absolutely naive of [the largemouth bass],” he said.

But the mosquitofish have had many generations to learn to fear largemouth bass, so they were impacted. During the study, the researchers periodically moved the mosquitofish into other tanks. The team saw that the invasive species displayed anxiety, staying in schools and rarely leaving the center of the tank. They also grew smaller and produced less sperm and fewer eggs. These issues persisted for weeks—not an insignificant amount of time for a fish that lives for about a year.

In theory, the robotic approach could be used for other fish and non-aquatic species, as pretty much every animal feels fear. But Polverino said there are no plans to release the robo-bass into the wild any time soon. So far, the robot has only been studied in the lab, and in the wild, there are many other factors to contend with.

“This is a proof of concept,” he said.

There are, however, some smaller bodies of water in Australia where this machine could be tested in a less complex system, such as the small ponds in the Edgbaston Conservation Area, home to the Edgbaston goby, a small, critically endangered fish. Releasing the robot in these bodies of water in the future might help protect endangered native species.

“But I doubt in the very short term—in the next couple of years—that this technology could be applied widely,” he said.

iScience, 2021. DOI: 10.1016/j.isci.2021.103529 (About DOIs)