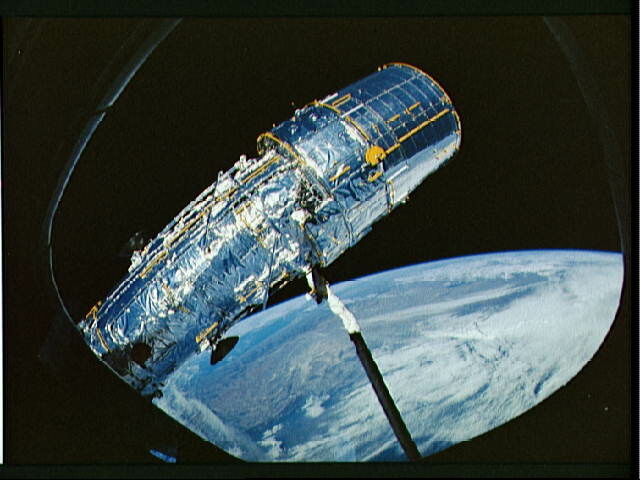

Space Shuttle Discovery launched into orbit 30 years ago today with the Hubble Space Telescope in its payload bay.

Charlie Bolden, who served as pilot for the STS-31 shuttle mission, remembers the five-day spaceflight like it was yesterday. “What stands out most vividly in my mind is all things that didn’t go right,” Bolden recalled in an interview.

It’s true. Although astronomers would not discover that the Hubble Space Telescope had a serious problem with its mirror until a few weeks after Discovery landed, the deployment mission was not without difficulties itself. The crew came within minutes of embarking on an emergency spacewalk and even had contingency plans to bring Hubble back to Earth if needed.

The mission was novel from the beginning, with a planned orbit at 612km above the planet’s surface requiring the vehicle to fly higher than any shuttle mission to date. Telescope deployment came a day after the shuttle reached orbit and involved a complicated sequence of events. After disconnecting the telescope from the shuttle’s power supply, astronauts would use a robotic arm to move the instrument from the shuttle’s payload pay, open its solar arrays, and finally release the telescope.

NASA

“From the time we disconnected Hubble from the shuttle’s power, we had two clocks running,” explained Bill Reeves, who was the mission’s flight director and supervised operations from Johnson Space Center. “The telescope was on battery power from that moment, and there was a limited supply. And with the telescope attached to the arm, the shuttle had to be on free drift, as thruster firings might damage the instrument.”

When ground controllers commanded the telescope to begin unfurling its two solar arrays, one of the arrays did not do so properly. Minutes turned into hours as engineers on the ground troubleshot the problem. Reeves had a contingency plan for this, of course. It entailed sending astronauts Bruce McCandless and and Kathryn Sullivan outside the shuttle to manually deploy the arrays.

A few hours into the ordeal, with the Hubble batteries draining and the shuttle beginning to rotate without attitude control, Reeves directed McCandless and Sullivan to suit up and enter the airlock. They depressurized down from 14.7psi down to 5psi and conducted their spacesuit leak checks—the final step before fully depressurizing the airlock, opening the hatch, and going out into space.

As Reeves contemplated whether to give this egress order, engineers said they thought they had identified a problem with the software that monitored tension in the solar array. Making a small change, they proposed, would fix the problem. This worked, and the second solar array unfurled beside its companion. However, because the telescope still had to be deployed and the robotic arm stowed, Reeves kept McCandless and Sullivan in the airlock, without even a window to watch as the Hubble telescope floated away.

Hubble Space Telescope solar array panel deployment during STS-31.

NASA

“They were the only two people on the planet that didn’t get to see the Hubble deploy,” Reeves said. To this day, he added, Sullivan still asks in jest if he did that on purpose.

After Hubble deployed, the shuttle retreated half an orbit away, in case some immediate problem arose that the crew needed to fix. (There wasn’t, as the scientific commissioning of the instrument would not happen for a couple of weeks). If Hubble’s problems were bad enough, the STS-31 crew had plans to bring the telescope back to Earth in Discovery’s payload bay. The shuttle was slated to land on the longer Edwards Air Force Base runway in California, instead of Florida, because of the possibility of coming back heavier, with a damaged Hubble in tow.

Because there were no apparent problems while they remained on orbit, the astronauts were given the all-clear to return five days after launching. Upon the shuttle touching down in California, Reeves recalls telling his flight controllers, “You people have no idea what you’ve just done.” The Hubble Space Telescope, he said, would change the way humans looked at the stars.

NASA

For a while, Bolden recalls being on top of the world after landing. Like everyone else, the astronauts eagerly awaited the first image from the telescope, a shot of a distant star named HD96755 captured on May 20, 1990. Their elation was crushed when the first picture turned out to be blurry and only marginally better than ground-based telescopes. Soon, astronomers realized the telescope had a warped mirror.

“The morale just went rock bottom,” said Bolden. “NASA became the brunt of jokes around the world. We were a big hit with all the nighttime talk shows for about three years.”

But then a funny thing happened. NASA activated its Apollo 13 muscle memory and, over the course of the next three years, planned a meticulous servicing mission to correct the mirror, upgrade its instruments, and bring a new and more powerful set of solar panels. In December 1993, Space Shuttle Endeavour flew an 11-day servicing mission that included five spacewalks. Story Musgrave, who had worked on Hubble’s development since the early 1970s, served as lead spacewalker.

-

A gallery of some of Hubble’s greatest hits: the galaxy cluster SDSS J1038+4849, with bright galaxies creating the eyes and nose, and gravitational lensing effects causing the curved features.

-

The iconic Pillars of Creation in the Eagle Nebula, taken with the Wide Field Planetary Camera 2.

-

The same location, imaged with the updated Wide Field Camera 3.

-

A Hubble image of Eta Carinae, a hypergiant star (over 100 times the mass of the Sun) that has suffered two major explosions, creating a large debris nebula. The star will eventually experience a supernova.

-

An image created to celebrate Hubble’s 16th birthday, this is a composite of the starburst galaxy Messier 82.

-

Point Hubble at a seemingly empty part of the sky and wait for 10 days. That’s the recipe behind the Hubble Deep Field image, which captures galaxies going back to the dawn of the Universe.

-

The gravitational interactions of these two galaxies in Arp 273 makes for this amazing image, which has been likened to a cosmic rose.

-

Hubble’s 20th anniversary photo is of a feature in the Carina Nebula, a star-forming region that includes Eta Carinae, which appeared earlier.

-

The Horsehead Nebula imaged in the infrared. This feature can be found within the constellation of Orion.

-

Arp 148, the aftermath of a collision between two galaxies.

-

Sometimes, the Hubble is targeted at objects closer to home. Here, the Great Red Spot of Jupiter is shown near two smaller companions.

-

The Arp catalog contains nothing but unusually shaped galaxies, which are generally the product of collisions. Here, two galaxies (NGC 6050 and IC 1179) combine to form the structure known as Arp 272.

-

A planetary nebula called NGC 6751. These features have nothing to do with planets. Instead, they are created when a large star ejects gas and then illuminates it from within.

-

This shows two galaxies colliding. The collision has set off a burst of star formation in the space in between them (seen in blue to the left of center). The collision has also created the long tail spiraling out of the galaxy to the right.

-

Westerlund 2, a cluster of newly formed stars, in a composite of images taken from more than one Hubble camera. The image was released to celebrate Hubble’s 25th year in space.

“The machine had a very bad start,” he said. “Putting the wrong mirror in the telescope was criminal negligence. I forgive mistakes, but that was much worse than a mistake. That’s not a good story.”

What followed, however, is a good story. Over the last 27 years, and four additional servicing missions, NASA and its astronauts have upgraded the instrument beyond the dreams of its original planners. Hubble has emerged as arguably the most important scientific instrument of all time, both enlightening astronomers about the nature of the universe as well transcending science into popular culture.

“I was not ready for the power of the observations,” Musgrave said. “Compared to some of the big telescopes on Earth, Hubble is such a tiny telescope. But it’s got a clear view. People love the images, not just for the science but for their beauty. It says something about who we are.”