In July, an HIV-positive man became the first volunteer in a clinical trial aimed at using Crispr gene editing to snip the AIDS-causing virus out of his cells. For an hour, he was hooked up to an IV bag that pumped the experimental treatment directly into his bloodstream. The one-time infusion is designed to carry the gene-editing tools to the man’s infected cells to clear the virus.

Later this month, the volunteer will stop taking the antiretroviral drugs he’s been on to keep the virus at undetectable levels. Then, investigators will wait 12 weeks to see if the virus rebounds. If not, they’ll consider the experiment a success. “What we’re trying to do is return the cell to a near-normal state,” says Daniel Dornbusch, CEO of Excision BioTherapeutics, the San Francisco-based biotech company that’s running the trial.

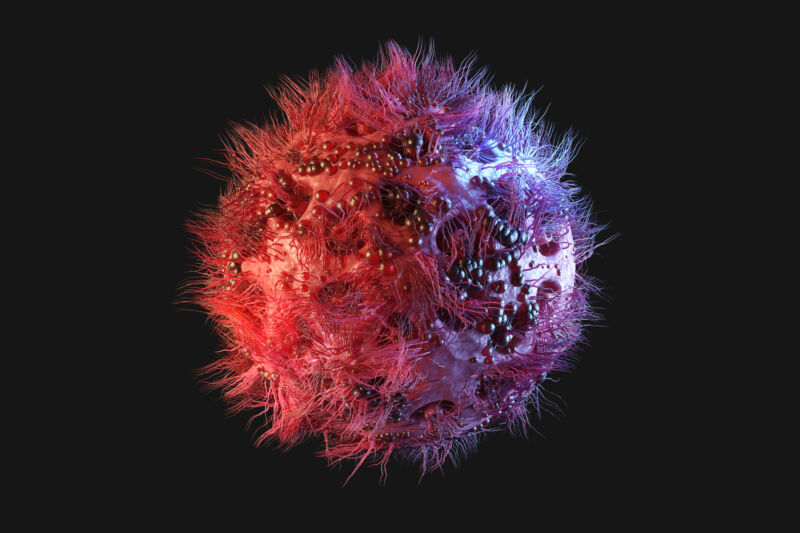

The HIV virus attacks immune cells in the body called CD4 cells and hijacks their machinery to make copies of itself. But some HIV-infected cells can go dormant—sometimes for years—and not actively produce new virus copies. These so-called reservoirs are a major barrier to curing HIV.

“HIV is a tough foe to fight because it’s able to insert itself into our own DNA, and it’s also able to become silent and reactivate at different points in a person’s life,” says Jonathan Li, a physician at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and HIV researcher at Harvard University who’s not involved with the Crispr trial. Figuring out how to target these reservoirs—and doing it without harming vital CD4 cells—has proven challenging, Li says.

While antiretroviral drugs can halt viral replication and clear the virus from the blood, they can’t reach these reservoirs, so people have to take medication every day for the rest of their lives. But Excision BioTherapeutics is hoping that Crispr will remove HIV for good.

Crispr is being used in several other studies to treat a handful of conditions that arise from genetic mutations. In those cases, scientists are using Crispr to edit peoples’ own cells. But for the HIV trial, Excision researchers are turning the gene-editing tool against the virus. The Crispr infusion contains gene-editing molecules that target two regions in the HIV genome important for viral replication. The virus can only reproduce if it’s fully intact, so Crispr disrupts that process by cutting out chunks of the genome.

In 2019, researchers at Temple University and the University of Nebraska found that using Crispr to delete those regions eliminated HIV from the genomes of rats and mice. A year later, the Temple group also showed that the approach safely removed viral DNA from macaques with SIV, the monkey version of HIV.