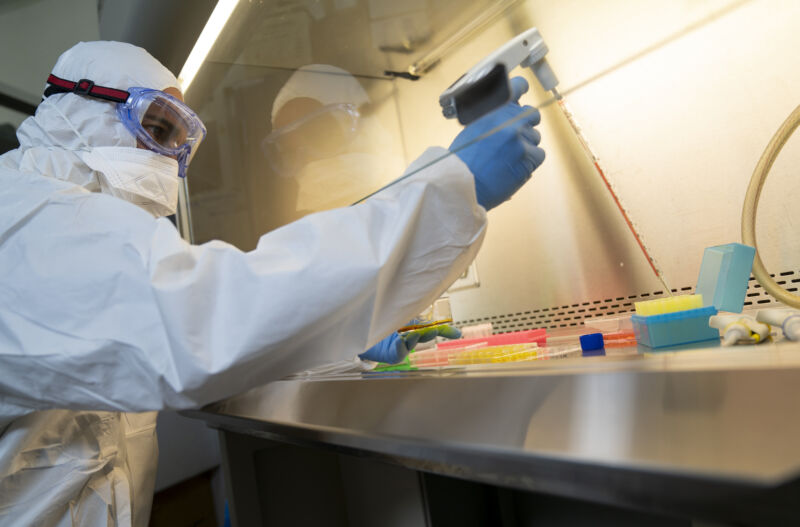

seksan Mongkhonkhamsao / Getty

Testing is one of the most important tools for getting the coronavirus pandemic under control in the United States. More than 160,000 COVID-19 tests were performed in the US on Thursday, according to the COVID Tracking Project. But there’s good reason to believe that there are still many people with the virus who have not been tested. More testing would help guide treatment and quarantine decisions and give government officials more data about the extent of the COVID-19 outbreak.

At the same time, a Nature investigation has revealed that a number of academic labs capable of performing COVID-19 tests are operating well below capacity. Nature’s reporting suggests that incompatible IT systems are significant reasons for this mismatch.

Many hospitals are used to working with large commercial labs that have the software necessary to interface with a hospital’s electronic health records and billing systems. When an academic lab shows up with the capacity to run tests but not the infrastructure to interface with hospital systems, hospitals are often reluctant to do business with them.

Nature talked to Fyodor Urnov, who directs a genomics center at the University of California, Berkeley. The organization launched a testing service in late March and began pitching it to hospitals. His lab already has the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA) certification that is required to perform COVID-19 tests.

The tests would have been free to hospitals, funded by private philanthropists. But he still had trouble finding hospitals interested in working with him.

“The business of American medicine and the way it is organized is astonishingly unprepared for this,” he told Nature. “I show up in a magic ship, with 20,000 free kits and CLIA and everything, and the major hospitals say: ‘Go away, we cannot interface with you.’”

Urnov’s lab wound up testing some patients outside the hospital system—including firefighters and homeless people. The non-profit group coordinating these tests doesn’t have software compatible with the Berkeley testing service’s software, but folks on both sides were willing to do manual data entry to accelerate the testing process.

Stacey Gabriel, a human geneticist at the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, told Nature that “our capacity is 2,000 tests a day, but we aren’t doing that many. Yesterday was around 1,000.”

Like Urnov’s group, Gabriel’s project has had to hustle to find partners willing to be flexible enough to try a service that didn’t have the full infrastructure of a commercial testing lab. “It took about 2,000 phone calls and many e-mails, but we’re getting there,” Gabriel told Nature.

But she worries that logistical difficulties like this could prevent other labs from joining the testing effort.