An eradicated form of wild polio surfaced in routine wastewater monitoring in the Netherlands last year, offering a cautionary tale on the importance of monitoring for the tenacious virus, researchers report this week in the journal Eurosurveilance.

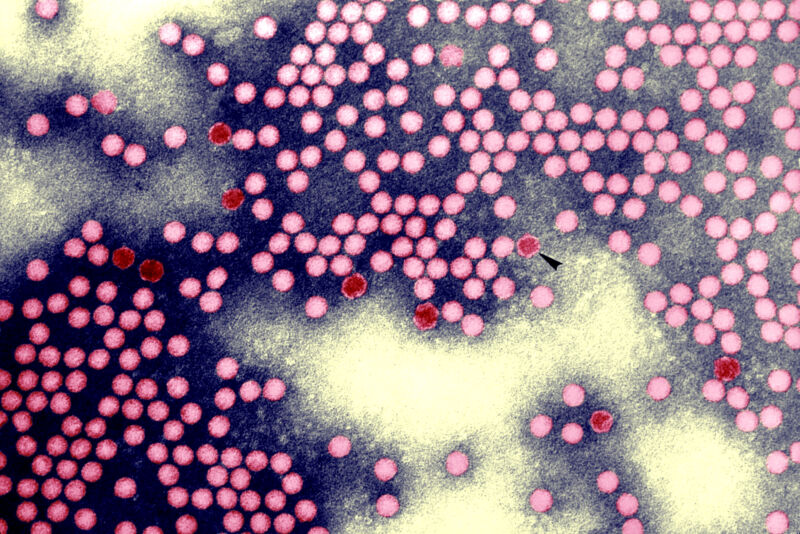

The sewage sample came up positive for infectious poliovirus in mid-November and genome sequencing revealed a strain of wild poliovirus type 3, which was declared globally eradicated in 2019. Its potential revival would be a devastating setback in the decades-long effort to stamp out highly infectious and potentially paralytic germ for good.

For brief background, there are three types of wild polioviruses: type 2 and type 3 have been eradicated, with the former being knocked out in 2015. Wild poliovirus type 1 continues to circulate in Afghanistan and Pakistan. There are also occasional vaccine-derived polioviruses that circulate in communities with low vaccination rates, which recently occurred in New York.

The positive wastewater sample last year was the first and only indication of a polio infection with the bygone strain in the Netherlands. It occurred in an employee of a vaccine production facility run by Bilthoven Biologicals, which makes inactivated polio vaccines. The Netherlands had set up routine wastewater surveillance around the production site to monitor for such a viral escape.

The genome sequencing made clear it was an active infection rather than a case of the virus being dumped down the drain somehow. The virus isolates had two to three mutations, suggesting human shedding. As such, officials worked to identify which employees had access to type 3 polio in the weeks before the positive sample. They narrowed it down to 51 employees and tested blood and stool samples from each. Only one came up positive.

It’s unclear how this employee became infected. The person was fully vaccinated against polio and had no symptoms. Still, they were shedding infectious virions of an otherwise eradicated virus in their stool, which could potentially spread to others. Moreover, the person lived in a community with vaccination coverage of less than 90 percent.

On December 8, the employee agreed to go into isolation with daily supervision from local health workers. Bilthoven Biologicals placed its infected employee in a house designed for isolation, situated in a community with more than 90 percent vaccination coverage. Local health workers made sure the person followed strict hygiene measures while they were still shedding viruses. The person’s feces were collected in a disposable system and incinerated. The person was only allowed to see people outside, with no physical contact.

The infected employee spent the next 33 days in isolation, including over the holidays, until they had three consecutive negative stool samples. Overall, the person shed the virus over 51 days. But contact tracing and further employee testing found no evidence of other infections, and wastewater sampling did not turn up any other positive samples.

In all, local health officials emphasized the importance of surveillance in this case. “This event shows that incidents that lead to a breach of containment and even an infection can remain unnoticed and not reported if routine monitoring is not in place,” they concluded.