National Geographic

Weipa is a small coastal mining town in Queensland, located in northeastern Australia, particularly favored by sports fisherman because of its annual competition, the Weipa Fishing Classic. But in recent years, fishermen have reported an increasing number of incidents where local bull sharks are pulling off audacious underwater raids, literally waiting until a fish is hooked and chomping it off the line. Some fisherman estimate they can lose as much as 70 percent of their catch to the sharks, which seem to specifically target fishing boats.

(Some spoilers for the documentary below the gallery.)

It’s atypical behavior for bull sharks and it raises an interesting question: is this evidence that this species of shark—known (a bit unfairly) in the popular imagination for being aggressive “mindless killers”—are more intelligent than previously assumed? That’s one of the questions that shark biologists Johan Gustafson and Mariel Familiar Lopez set out to answer, and their initial field work has been documented for posterity in Bull Shark Bandits, part of National Geographic’s 2023 SHARKFEST programming. SHARKFEST is four full weeks of “explosive, hair-raising and celebratory shark programming that … showcase the captivating science, power and beauty of these magnificent animals,” per the official description.

The fish-stealing behavior is technically known as depredation. Among other factors, Australian fish stocks have decreased by more than 30 percent over the last decade, and the sharks appear to be adapting accordingly and teaching the behavior to their fellow sharks.

“Many different species do it, including dolphins and orcas, high level predators, but shark depredation in particular is occurring all over Australia at the moment,” Gustafson told Ars. “In areas where there’s a higher fishing pressure, the behavior is occurring more often or more intensely. We call it habituation. They’ve learned a habit, they actually learn off each other, and they spread it around [the population].”

Bull sharks (Carcharhinus leucas) are found all over the world, usually preferring warm, shallow, coastal waters and freshwater rivers. They’re not a true freshwater species, but the females typically birth their pups upriver since such spots provide a more protective environment for nurseries. (Sharks don’t rear their young; baby sharks typically join the adult ocean population when they reach about eight years of age.) Bull sharks usually grow to an average of seven feet (for males) and eight feet long (for females), and their powerful bite can generate as much as 1330 pounds of force (5914 newtons).

-

Dr. Mariel Familiar Lopez with the Weipa shoreline in the background

National Geographic -

Dr. Johan Gustafson prepares to tag a bull shark.

National Geographic -

Lopez and Gustafson inspect an underwater camera.

National Geographic -

Gustafson holds a bull shark while Lopez prepares to measure it.

National Geographic

Bull sharks are considered opportunistic feeders, meaning they eat in short burts and digest for longer periods during times of scarcity. Their diet favors bony fish and smaller sharks (including their fellow bull sharks), as well as turtles, birds, dolphins and crustaceans. They’re also fairly territorial and solitary, preferring to hunt alone or occasionally in pairs.

Their reputation for aggression has been fueled in part by media reports of bull shark attacks, including the 1916 Jersey Shore shark attacks that inspired Jaws—both the novel by Peter Benchley and the 1975 blockbuster film (although both actually featured a Great White shark). Bull sharks are indeed responsible for many shark attacks near coastal shores, and they have a ferocious bite. But the reality is more nuanced. “I always tell people that every animal, every human or every dog, we all have different personalities,” Lopez told Ars. “So you might get a bull shark that is really aggressive, but you might get one that is not. Their main focus is always catching meals. But they’re not, like, ‘Oh, I’m going to be aggressive to every single thing that I see.'”

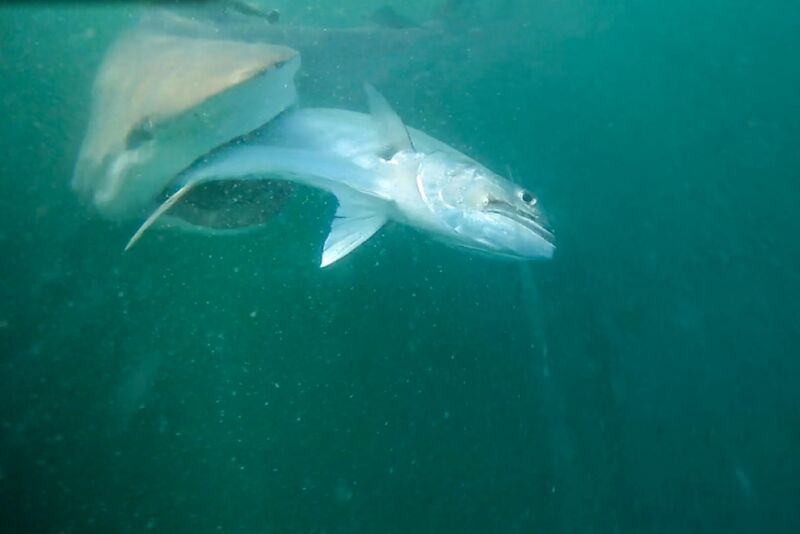

It wasn’t entirely clear from the various accounts if it really was bull sharks stealing the fish, since it all happens underwater. So the first order of business for Gustafson and Lopez was to verify the anecdotal reports and try to catch a bull shark in the act. They used a fishing line camera to capture a low-resolution shot of a bull shark stealing a hooked fish in just 20 seconds, but they needed to get into the water to capture more footage with a 360-degree drop camera. A shark cage was in order, but most metal cages are fairly noisy in terms of sound reflection. That’s fine with some regional sharks who are used to the cages, per Gustafson, but the Weiba bull shark population is more isolated and more likely to be spooked by the noise.

So Gustafson and Lopez turned to underwater cinematographer Colin Thrupp, who constructed a novel noise-cancelling shark cage out of polyethylene pipe with the joints welded via electro-fusion welding. The plastic absorbs sound more than a metal cage, and the black color also means less reflective shine. The cage served its purpose; the bull sharks were initially cautious but the camera ultimately caught six or seven of them swimming nearby as a pack—unusual behavior for a such a solitary and territorial species. “Part of our hypothesis is that this is a population of bull sharks that don’t really migrate that much, because they’ve got warm water conditions all year round, it’s a nice tropical area,” said Lopez. “That is maybe one of the factors [providing] opportunity for socialization. They might be getting a bit of toleration between each other because they’re getting an easy meal.”

-

A bull shark, captured on camera from the custom-made shark cage.

National Geographic -

A bull shark swims past the custom-made shark cage.

National Geographic -

Lopez prepares to take a DNA sample from a bull shark caught by the team.

National Geographic

The footage also showed a bull shark approaching the hooked fish slowly at first, waiting for it to get tired of struggling, and then biting off the fish’s tail end and propeller, before swinging back around to gulp down the rest. This is a calm, intelligent hunting strategy, per Gustafson and Lopez, the antithesis of the stereotypical mindless aggression usually associated with bull sharks. In fact, it’s strikingly similar to how killer whales—known for their intelligence—hunt, employing a surgically precise approach to save energy. “Being a top predator means you invest a lot of energy in all those catches,” said Lopez. “If that doesn’t come with a reward, you’ll have less energy for the next chase. So they have to be very intelligent [to determine] ‘Where do I put my energy in all this?’ Sometimes, when they’re not sure, they do these test bites.”

The plastic cage didn’t perform perfectly, however, starting to bounce around and buckle as swells developed and underwater turbulence increased. The communications link to the surface also went out, resulting in some tense moments until the cage was brought back to the surface. “We were in that cage and it was gloomy and the current was huge,” Gustafson recalled. “Then we saw a cable tie fly past us and thought, ‘Oh, that’s not good,’ because they’re actually what’s holding the cage [mesh] together. Then another one went by. Then the cage started to deform. It was like being in a [trash] compactor.”

Gustafson and Lopez also managed to tag several sharks with acoustic transmitters to track their movements. Since they had spotted a juvenile shark among the adults, they also located the most likely bull shark nursery in a nearby river, taking a biopsy from one baby shark for DNA analysis. Once Thrupp had repaired and strengthened the plastic shark cage, they deployed it a second time to take biopsies of two other sharks for comparison, using harpoon-like tools.

The results showed that the juvenile they biopsied upriver was half-related to the female bull shark they biopsied back in the ocean, while the third sampled shark was related to both of them. So all three sharks likely share an ancenstor between them. This is yet more evidence that the population at Weiba isn’t moving around much, because there is more opportunity for interbreeding, particularly since shark litters typically have multiple fathers, per Gustafson.

Clip from Bull Shark Bandits

The next step includes gathering more DNA samples from the Weiba bull shark population to expand the genetic analysis, as well as tagging and tracking more bull sharks to get a sense of their movement patterns in order to determine how the top end of the gulf ecosystem (Weiba) connects to the western and eastern sides of the continent. “Do they go all the way down to Perth on the west or right down to Sydney?” said Gustafson. “Turtles tend to come back to the same beach where they were born. We think these bull sharks are starting to do the same sort of a thing. But we don’t know if they’re coming back to the same river that they were born in, or into the same area that they were born in.”

More data should also give them a better idea of the size of the bull shark population in Weiba, since the popular perception among fishermen is that there must be hundreds or thousands of them. And as fishermen keep losing their catches, there is a greater risk of more anger being directed at the bull sharks, leading to decreased support for their conservation and more calls for culling the population. (The species is listed as vulnerable on the IUCN Red List.)

“The more you spend time in the water, the probability that you will encounter a shark becomes greater,” said Lopez. “But that is just because you’re spending more time in the water fishing. It doesn’t mean there are more sharks lurking in the waters and being aggressive. It’s important to do these documentaries because you’ll never change the mind of people if you just say sharks are not bad. You need to include them in a little bit of the science, explain it. For projects like this, we go up there and spend time at the pubs talking to the fishermen. We’ve even got some fishermen helping us take samples.”

Bull Shark Bandits is now streaming on Disney+ and Hulu, premiering on NatGeo WILD on July 25, 2023.