Jørn Ladegaard

Over 100 years ago, a Danish explorer named Jørgen Brønlund perished during an expedition to northeast Greenland, along with two members of his expedition. He left behind a diary detailing his last moments, with a black spot underneath his final signature. Scientists have now analyzed that spot using a variety of techniques to determine its composition, thereby shedding fresh light on Brønlund’s final hours, according to a November paper published in the journal Archaeometry.

Northeast Greenland is still one of the most hostile regions of the Arctic, with only the Sirius Patrol of the Danish Army occasionally crossing the frozen expanse on dog sledges during the coldest part of the year. Back in 1906, when the Denmark Expedition launched, many parts of the region had not yet been mapped; that was a primary objective of the expedition, along with various scientific studies. (Alfred Wegener was among the scientists in the expedition.)

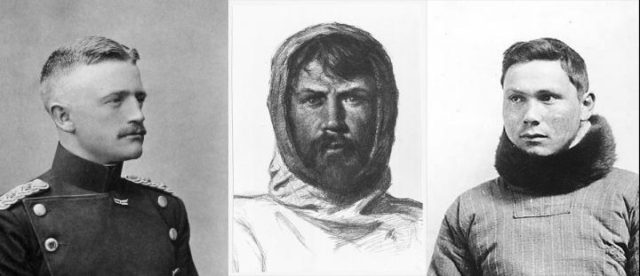

The expedition sailed to Greenland on board the SS Danmark, landing in August 1906 and establishing a base camp (depot) called Danmarkshavn. Members were assigned to sledge teams to head northward. Jørgen Brønlund was part of Sledge Team 1, along with expedition commander Ludvig Mylius-Erichsen and Niels Peter Høeg Hagen. A significant part of their mission was to discover whether the so-called Peary Land (discovered by Robert Peary in 1891) was a peninsula—in which case it would remain part of the Danish Kingdom—or an island, in which case the US would claim it as a US territory.

Public Domain/Wikipedia

The sledge teams headed north in March 1907, hampered by buckling and cracking ice as well as broken-down sledges. Mylius-Erichsen, Brønlund, and Høeg Hagen decided to follow the shoreline, but the commander became increasingly concerned as that route unexpectedly led them northeast. That meant a greater distance to their ultimate goal, as time and provisions grew short. When he and his two sledge mates entered the unmapped Danmark Fjord, it turned out to be a dead end, forcing them to backtrack northeast to return to the mouth of the fjord—wasting precious time. Melting ice would make passage back to Danmarkshavn impossible, and they didn’t want to get stuck in the area without sufficient food and supplies.

That’s when Mylius-Erichsen made the fateful decision not to return to the ship, but to head west in hopes of reaching Navy Cliff at the head of Independence Fjord. By this time the summer thaw had set in, and hunting conditions were poor, plus their shoes had worn through from trekking over the stony ground. In short, as Brønlund noted in his diary, their situation was dire: “no food, no foot gear, and several hundred miles to the ship. Our prospects are very bad indeed.”

By September, they were forced to try to cross the frozen waters of the 79-Fjord. They were down to one sledge and four dogs. Høeg Hagen died first, from exhaustion, on November 15, 1907, with Mylius-Erichsen passing ten days later. Brønlund actually made it to the other side of the fjord, to one of the expedition’s existing depots. But the darkness and severe frostbite in his feet prevented him from going any further. He took shelter in a cave and wrote his final diary entry:

I perished in 77° N lat., under the hardships of the return journey over the inland ice in November. I reached this place under a waning moon, and cannot go on, because of my frozen feet and the darkness. The bodies of the others are in the middle of the fjord. Hagen died on November 15, Mylius-Erichsen some ten days later.

The following spring, two other expedition members found Brønlund’s body, with the diary safely stored in the sledge at his feet. They buried him where he died, and the headland is known today as Brønlund’s Grave. As for the rest of the Danish Expedition, it was remarkably successful—some 51 reports were published—although that success was overshadowed by the tragic deaths of Brønlund, Mylius-Erichsen, and Høeg Hagen.

The 172-page diary is currently housed in the Royal Library in Copenhagen. Below Brønlund’s signature was an odd-looking black spot. In 1993, the spot was removed with a pocket knife by a reader. “This was done without permission which is of course both unorthodox and illegal,” the authors noted in their paper. Fortunately, the sample ended up with the National Museum of Denmark’s Natural Science Unit, but despite being examined by many experts, no conclusions could be drawn about what the material might be.

Kaare Lund Rasmussen/SDU

That’s where the current study comes in. Back in 2018, Kaare Lund Rasmussen and several colleagues at the University of Southern Denmark collaborated with the National Museum and Royal Library to make a definitive determination of the sample’s composition. The team took small samples from the black spot and analyzed them with X-ray fluorescence, synchrotron radiation powder x-ray diffraction, Raman spectroscopy, and gas chromatography mass spectrometry, among other methods.

They discovered that the spot was made up of burnt rubber, vegetable oil, fish or animal fats, petroleum, and feces. There was also goethite, a mineral common to the environment. The burnt rubber likely came from a gasket in the Lux burner Brønlund had among his supplies, and may have been burnt as the doomed explorer struggled to light a fire to keep warm, using any potentially flammable materials available to him. (The burner was recovered in 1973 by the Sirius Patrol.) The authors surmise that Brønlund was in the cave roughly five or six days before he died, given that the sledge case was barely half-empty.

“This new knowledge gives a unique insight into Brønlund’s last hours,” said Rasmussen. “I see for me, how he, weakened and with dirty, shaking hands, fumbled in an attempt to light the burner, but failed. He had to find something else to get the burner going. You can use paper or oiled fabric, but it is difficult. We think he tried with the oils available, because the black spot contains traces of vegetable oil and oils that may come from fish, animals or wax candles.”

DOI: Archaeometry, 2020. 10.1111/arcm.12641 (About DOIs).