Julio Lacerda/NLD

Neanderthal hunters living 48,000 years ago in what is now Germany killed a large cave lion in what might be the earliest example of lion hunting yet known, according to a recent paper published in the journal Scientific Reports. Gabriele Russo of the University of Tubingen and co-authors based their conclusions on a close forensic analysis of a cave lion skeleton showing evidence of injury by a wooden spear. They also examined recently discovered cave lion claw bones showing evidence of having been skinned around 190,000 years ago.

Now extinct, cave lions were apex predators, larger than today’s mountain lions. They were frequently depicted in Paleolithic art, and their body parts were used as ornaments, according to the authors—part of a long-standing relationship between carnivores and hominids that shaped cultural behaviors. Although it’s known that hominins have been interacting with lions since the animals first arrived in Europe, less is known about the relationships between carnivores and hominims like Neanderthals from earlier periods.

Neanderthals were expert hunters known to kill bears and other carnivores, but evidence for them interacting with cave lions has remained scarce. A pair of lion fibula from the Middle Paleolithic found in eastern Iberia with cut marks indicates the lion was butchered, while other lion bones found in Southwestern France from the same period had cut marks indicative of skinning. This latest paper focused on a re-evaluation of a medium-sized male cave lion skeleton found at Siegsdorf, in Central Germany, in the 1980s.

Volker Minkus/NLD

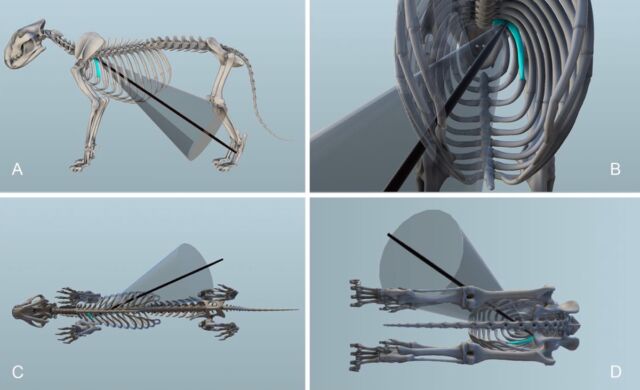

Archaeologists had already noticed cut marks on several of the bones (two ribs, the left femur, and a few vertebrae) suggestive of butchering after the animal had died—in other words, it’s evidence of scavenging rather than active hunting. But Russo et al. also found evidence of hunting lesions, most notably a partial puncture wound on the inside of the third rib typical of the impact from a wooden-tipped spear, based on similar marks found on deer vertebrae. The puncture is too deep to be attributed to tooth marks of another carnivorous animal and also lacks the telltale pits and perforations from such teeth.

The team tested their hypothesis by reconstructing the ballistics of a wooden-tipped spear’s impact on the rib, matching the direction, impact angle, and depth of penetration. Judging by those aspects, it looks like the spear went through the left side of the cave lion’s abdomen and passed through vital organs before hitting the right side of the rib. “This would have been a lethal wound for the animal,” the authors concluded. They did find some evidence of drag marks as well, and since both throwing and thrusting weapons were often used side by side, “it remains possible that [the] drag marks may indicate that spears were thrown at the lion,” they wrote.

G. Russo et al., 2023

The team also analyzed cave lion claw bones they discovered in the Einhornhöhle Cave in Germany in 2019 that are at least 190,000 years old, based on the layer of sediment in which they were found. Those bones showed cut marks consistent with skinning, with care taken to preserve the claws within the fur. The authors believe this could be the earliest example of Neanderthals’ use of a cave lion pelt in Central Europe, possibly for cultural purposes.

“The absence of polish, wear, perforations, or any distinctive features associated with pendants or clothing components in the lion claws… sets them apart from examples found in the archaeological and ethnographic record, suggesting their unlikely use as such,” Russo et al. wrote, suggesting that the carcass was likely skinned elsewhere from a fresh kill with only the pelt, or possibly just the paws, being brought back to the cave. “We conclude that Neanderthals were capable of engaging with non-human predators such as lions not only economically but also culturally—as Homo sapiens also is evidenced to have done later in time.”

DOI: Scientific Reports, 2023. 10.1038/s41598-023-42764-0 (About DOIs).